Management of Pregnancy of Unknown Location (PUL)

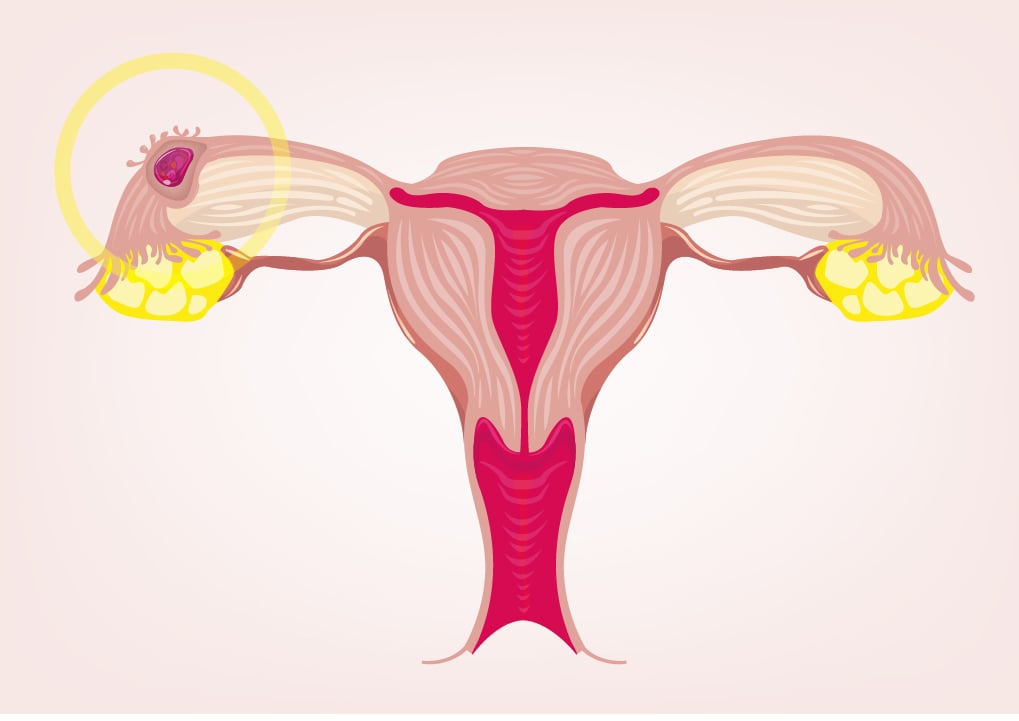

Your pregnancy test is positive, but when you come into the doctor’s office for an ultrasound, the pregnancy does not appear to be implanted in the uterus. Your physician or sonographer mentions the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy, which is when the embryo is implanted outside of the uterus. This phenomenon is known as a “pregnancy of unknown location,” or a PUL. There is no need for panic, PUL is most commonly a transient situation that is safely and well-managed.

There are four main classifications of PULs: defined ectopic pregnancy, probable ectopic pregnancy, defined intrauterine pregnancy, and probable intrauterine pregnancy. (1) Ectopic pregnancies comprise the smallest proportion of cases, with a prevalence of only 1 - 2% of all PULs. (2) Certain intrauterine pregnancies are initially defined as PULs simply because it is too early in the pregnancy to see them on an ultrasound. (2) The majority of PULs are low-risk, and in fact, often resolve on their own. Beyond this, the strategies used to manage and monitor the development of PULs today are both clinically-validated and successful.

The use of transvaginal ultrasounds (TVS) is a highly specific and sensitive method to identify ectopic pregnancies. TVS are able to identify ectopic pregnancies with sensitivity ranging from 87 - 94% and specificity ranging from 94 - 99%, meaning that a defined ectopic pregnancy PUL may be identifiable even within a single examination. (1) In fact, it is believed that up to 90% of ectopic pregnancies can be confirm during the initial ultrasound. (2)

Probable ectopic pregnancies, on the other hand, are those that are not seen via TVS. Fortunately, methods have been developed to risk-stratify and predict ectopic pregnancies in this scenario. One of the most widely trusted methods is the use of the M6 risk model (an updated version of the M4 risk model), which stratifies a PUL as either high-risk or low-risk of ectopic pregnancy. (3) The M6 model is based on change of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels over time (normally 48 hours) and has the best overall performance for predicting an ectopic pregnancy. (4, 5) The outcomes of this model are used to guide subsequent treatment decisions, with a risk of >5% defined as a high risk of ectopic pregnancy. (6)

Management of ectopic pregnancies or intrauterine pregnancies may be medical, expectant, or surgical. (7) Medical management includes the use of Methotrexate, which is commonly used to manage ectopic pregnancies that do not require surgical intervention. (8) Methotrexate is a safe and effective method to manage ectopic pregnancies by interfering with cell growth. (3) Expectant management implies consistent monitoring of hCG changes until the management of the pregnancy is complete. This treatment can often eliminate the need for surgical intervention,. (3) The difference between medical and expectant management has been studied in randomized controlled trials, the results of which indicate that there is no difference in outcomes between the use of methotrexate and expectant management in cases of ectopic pregnancy. (9, 10)

Remember - PUL is not a definitive diagnosis. Advancements in technology enable physicians to either successfully locate a PUL (via ultrasound) or understand the likely type of PUL (via risk models and expectant management) so that proper management decisions can be made. The methods of management available today are both safe and effective, so it is best to stay informed and aware when faced with a diagnosis of PUL.

Resources

- Pereira, P. P., Cabar, F.R., Gomez, U. T., & Francisco, R. P. V. (2019). Pregnancy of unknown location. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 74, e1111.

- Barnhart, K., van Mello, N. M., Bourne, T., Kirk, E., Van Calster, B., Bottomley, C., Chung, K., Condous, G., Goldstein, S., Hajenius, P. J., Mol, B. W., Molinaro, T., O'Flynn O'Brien, K. L., Husicka, R., Sammel, M., & Timmerman, D. (2011). Pregnancy of unknown location: a consensus statement of nomenclature, definitions, and outcome. Fertility and sterility, 95(3), 857-866.

- Po, L., Thomas, J., Mills, K., Tulandi, T., Shuman, M., & Page, A., (2021). Guideline No. 414: management of pregnancy of unknown location and tubal and nontubal ectopic pregnancies. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 43(5), 614-630.

- Condous, G., Timmerman, D., Valentin, L., Jurkovic, D., & Bourne, T. (2006). Pregnancies of unknown location: consensus statement. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 28(2), 121-122.

- Ross, J. A. (2018). Diagnostic protocols for the management of pregnancy of unknown location. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 126(2), 199-199.

- Bobdiwala, S., Saso, S., Berbakel, J. Y., Al-Memar, M., Van Calster, B., Timmerman, D., & Bourne, T. (2018). Diagnostic protocols for the management of pregnancy of unknown location: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 126(2), 190-198.

- Bobdiwala, S., Al-Memar, M., Farren, J., & Bourne, T. (2017). Factors to consider in pregnancy of unknown location. Women’s health (London), 13(2), 27-33.

- Ectopic Pregnancy. (2018, February). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

- Barnhart, K. T., Sammel, M. D., Stephenson, M., Robins, J., Hansen, K. R., Youssef, W. A., Santoro, N., Eisenberg, E., & Zhang, H. (2018). Optimal treatment for women with persisting pregnancy of unknown location, a randomized controlled trial: the ACT-or-NOT trial. Contemporary clinical trials, 73, 145-151.

- Van Mello, N. M., Mol, F., Verhoeve, H. R., van Wely, M., Adriaanse, A. H., Boss, E. A., Dijkman, A. B., Bayram, N., Emanuel, M. H., Friederich, J., van der Leeuw-Harmsen, L., Lips, J. P., van Kessel, M. A., Ankum, W. M., van der Veen, F., Mol, B. W., & Hajenius, P. J. (2013). Methotrexate or expectant management in women with an ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location and low serum hCG concentrations? A randomized comparison. Human Reproduction, 28(1), 60-67.